Vincent van Gogh: The Mad Genius Who Redefined Art

Share

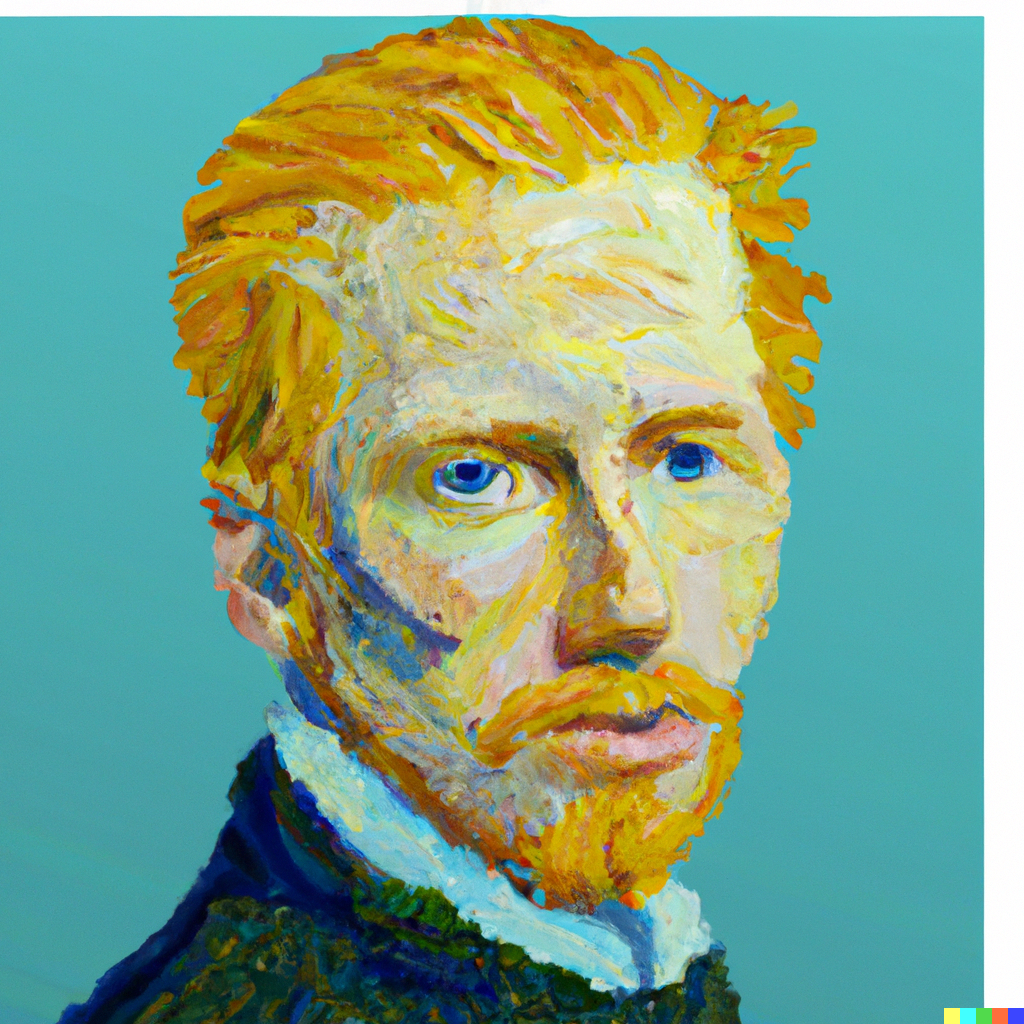

Few artists have captured the world’s imagination quite like Vincent van Gogh. The fiery-haired Dutchman, whose tragic life has become as legendary as his art, was a painter of paradoxes—both deeply misunderstood and profoundly influential. He painted with an urgency that bordered on desperation, as if each brushstroke might help him stave off the darkness that consumed his mind. And yet, in his own lifetime, he was dismissed, ignored, and largely unrecognized. It is a cruel irony that van Gogh, a man who longed for acceptance, would only find it after his death.

A Life Marked by Struggle

Born in 1853 in the quiet Dutch town of Zundert, Vincent Willem van Gogh was the son of a Protestant minister. From an early age, he was drawn to both spirituality and art, though neither would bring him lasting fulfillment. His early career was marked by restlessness—he worked as an art dealer, a teacher, and even a missionary before committing fully to painting in his late twenties.

His artistic journey was unconventional. Unlike his contemporaries, who trained in prestigious academies, van Gogh was largely self-taught. He devoured books on color theory and studied the works of artists he admired, but his style remained defiantly his own. He painted not with delicate precision but with raw emotion, wielding his brush like a weapon against an indifferent world.

The Political and Artistic Landscape of His Era

Van Gogh’s time was one of upheaval, both politically and artistically. The late 19th century saw Europe in transition—industrialization was reshaping cities, new political movements were challenging old power structures, and colonial expansion was at its height. In France, where van Gogh spent his most productive years, the Third Republic was in full swing, navigating the tensions between modernity and tradition.

In the art world, Impressionism had broken the dominance of academic painting, and the seeds of Post-Impressionism—a movement van Gogh would help define—were beginning to take root. Painters like Monet and Renoir had introduced the idea of capturing fleeting moments with dabs of pure color, but van Gogh went further. His work was not just about light and atmosphere; it was about emotion, about the turmoil inside him spilling onto the canvas. He rejected the polished realism of the past in favor of something rawer, something that felt alive.

The Tragic Journey to Recognition

It is difficult to pinpoint exactly when van Gogh was "discovered." During his lifetime, he remained on the fringes of the Parisian art scene, despite the support of his younger brother, Theo van Gogh, an art dealer who tirelessly promoted his work. Van Gogh exhibited with the Salon des Indépendants and was admired by a small circle of avant-garde artists, including Paul Gauguin, Émile Bernard, and Henri Toulouse-Lautrec. But the public did not embrace him.

His personal struggles overshadowed his artistic achievements. Prone to bouts of mania and depression, van Gogh’s mental health deteriorated rapidly. The infamous incident in Arles in 1888, where he severed part of his own ear after a confrontation with Gauguin, cemented his reputation as a madman. He spent time in asylums, painting feverishly even as his mind unraveled. His letters—especially those to Theo—reveal a man desperately searching for meaning, for connection, for peace.

On July 27, 1890, at just 37 years old, Vincent van Gogh shot himself in the chest in a wheat field near Auvers-sur-Oise. He died two days later, with Theo at his side. His final words—"La tristesse durera toujours" ("The sadness will last forever")—were a fitting epitaph for a life filled with longing and loss.

Masterpieces That Changed Art Forever

The Starry Night (1889)

Few paintings have been reproduced, analyzed, and revered as much as The Starry Night. Created while van Gogh was a patient at the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, it is a vision of the night sky as seen through the lens of his tortured psyche. The swirling blues, the pulsating stars, the restless energy—this is not a mere landscape; it is a self-portrait of the artist’s mind.

Critics and scholars have debated its meaning for decades. Is it a depiction of hope, or despair? A dream, or a hallucination? Perhaps it is all of these things at once. What is certain is that The Starry Night transcends time, continuing to mesmerize audiences more than a century later.

Sunflowers (1888)

Van Gogh’s series of sunflower paintings, created in Arles, are among his most famous works. These were not simply still lifes; they were experiments in color, in texture, in the power of simplicity. He painted them in bold, unmixed yellows, capturing both the vibrancy and fragility of life.

Sunflowers became a symbol of van Gogh himself—bright and brilliant, but destined to wither too soon. Today, these paintings are housed in major museums around the world, from the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam to the National Gallery in London.

Wheatfield with Crows (1890)

Often interpreted as van Gogh’s final painting, Wheatfield with Crows is a haunting image. The stormy sky, the golden wheat field, the ominous black crows—it is a landscape heavy with foreboding. Some see it as a suicide note in paint, others as a defiant statement of artistic freedom. Either way, it remains one of the most powerful depictions of nature ever put to canvas.

A Posthumous Rise to Fame

Van Gogh’s fame did not come in his lifetime, but in the years following his death, Theo’s widow, Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, played a crucial role in promoting his work. She organized exhibitions, published his letters, and tirelessly championed his genius. Slowly but surely, the art world began to recognize what it had ignored.

By the early 20th century, van Gogh’s influence was undeniable. The Fauvist and Expressionist movements drew directly from his wild use of color. The likes of Picasso and Matisse cited him as an inspiration. His reputation soared, his paintings became sought-after treasures, and today, they command record-breaking prices at auctions.

The Myth and the Man

In the public imagination, Vincent van Gogh is often reduced to the "tortured artist" archetype—a man who suffered for his art, who lived in obscurity and died alone. But this is only part of the story. Yes, he suffered, but he also created. He battled demons, but he also loved—his family, his friends, the simple beauty of a wheat field under a summer sky.

Today, his work is more than just a collection of paintings; it is a testament to resilience, to passion, to the idea that art can exist outside of recognition, outside of commerce, outside of fame. Van Gogh painted because he had to, because it was the only way he knew to make sense of the world. And in doing so, he gave the world something that will never fade.

Vincent van Gogh did not live to see his own success. But if he were alive today, standing in a crowded gallery as visitors whispered in awe before The Starry Night, one likes to think he would finally feel at peace.